Resisting assisted suicide

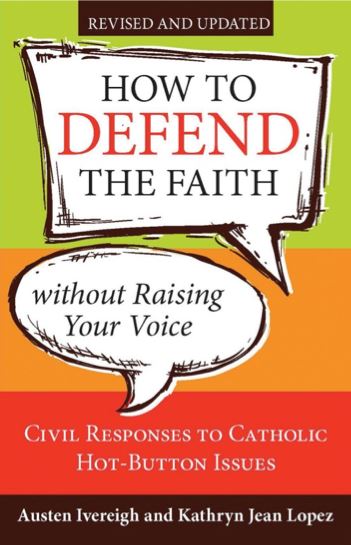

Tomorrow the UK Parliament debates a Bill tabled by the MP Robert Marris to legalise assisted suicide. The following is an excerpt from the new edition of a book by UK and US Catholic Voices coordinators Austen Ivereigh and Kathryn Jean Lopez called How to Defend the Faith Without Raising Your Voice, published by Our Sunday Visitor in the United States.

[Excerpt from Chapter 8: ‘Lights at the End of the Road: Resisting Assisted Suicide’]

The drive to make it legal to help someone commit suicide is one of the main ethical debates of our time, comparable, in its way, to the debate over legalizing abortion in the 1960s. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1997 that states could prohibit physician-assisted suicide; there is no constitutional right, therefore, to ask a doctor to administer drugs that cause death. But physician-assisted suicide is legal in Oregon, Washington, Vermont and Montana, and many other states are considering it. At either end of a decade, the emotional pull of stories of Terri Schiavo in 2005, a woman whose own family was split over her wishes and was finally left to starve to death after failed government attempts to intervene, and Brittany Maynard, who moved to Oregon to kill herself before her brain cancer did, became icons of how not to die and how to choose to die, respectively. In 2014,People magazine covers profiled the last days of Maynard, a twenty-nine year old newlywed who legally took her lethal prescription a few weeks before Thanksgiving.

Like abortion, the case in favor of assisted suicide is made by an appeal to a narrow ethic of autonomy: If a person is suffering unbearably, and wishes to end their life at a particular point, and in the manner of their choosing, who has any right to decide they can’t? But the way the question is framed is deceptive. There is little, in practice, anyone can do to prevent someone determined to commit suicide. But the demand for assisted suicide is different: it is asking the law, and the medical profession, to recognize and enable that suicide. Not only does the decision involve others, notably doctors; it also requires changing the supposition of the law, which is the defense of life.

The call for assisted suicide reflects, of course, the rise of the ethic of autonomy to the exclusion of other ethical considerations. It is being driven by three main changes in society. The first comes from modern advances in medical technology, in which an aging population means a greater prevalence of long-term, terminal conditions such as cancer, motor neuron disease, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s, which bring about great changes in a person and undoubted suffering. A man or woman nowadays faces years of incurable and long-lasting illnesses and suffering in a way that would be unknown in previous eras.

The second factor is a decreasing familiarity with death and dying, which increasingly takes place in hospitals, which are poorly equipped to deal with it. With unfamiliarity goes fear.

The third factor is material prosperity, and with it a growing resistance to the idea of dependency and vulnerability, along with a desire for choice and control. It is not a coincidence that the legalization of assisted suicide has occurred in wealthy countries and states. The loss of capacities and abilities that a person has set great store by is especially traumatic for high-achieving societies in which people build their lives around usefulness, success, and power. The question they, and society as a whole, face, is whether such lives are less worth living once these vanish. Whatever an individual may (in passing, or permanently) conclude, what happens when our laws endorse that idea?

Until the 1960s, assisted suicide — or ‘voluntary euthanasia’ as it was then known — was one of the options advanced by the eugenics movement to help rid society of “undesirables.” “The moment we face it frankly we are driven to the conclusion that the community has a right to put a price on the right to live in it,” wrote the playwright and eugenicist George Bernard Shaw in 1934. “If people are fit to live, let them live under decent human conditions. If they are not fit to live, kill them in a decent human way.”

Of course, advocates of legalizing euthanasia reject the comparison with the eugenicists of the 1920s and 1930s who paved the way for the Nazi death camps; where eugenicists favored compulsory sterilization, abortion and euthanasia, the modern case for assisted dying rests, like that of abortion, on the “right to choose.” Yet in both cases — the eugenicist call for euthanasia and the modern call for assisted suicide — a judgment is being made about the lack of worth of a human life. It may seem amazing now to recall that between 1915 and 1919 a Chicago surgeon, Harry Haiselden, publicly allowed six infants he diagnosed as hereditarily unfit to die by withholding treatment, and went on to make a movie, Black Stork, about a doctor who did the same (it was still being shown in American cinemas in the 1940s). In the case of an assisted suicide, a depressed or sick person is making the same decision about themselves. They have internalized the message that their life is not worth preserving. If the law condones that conclusion, what effect will that have on the way society views the elderly — or indeed the poor, the disabled, and the unsuccessful?

In this context the Church once again represents a counter-cultural logic. In the world of antiquity, Christians cared for disabled children, rather than engaging in the practice of infanticide, and stayed in areas afflicted by epidemics to care for the sick and dying, at risk to their own lives. The hope of the Christian message has always been that something of infinite goodness is possible even in the darkest of hours, even in the hour of death, and that in dying we learn the meaning of love and compassion. The hope of the Resurrection is the opposite of assisted suicide: it is not a longing to reverse or escape from physical death but to comfort and accompany the dying. Such is the choice that assisted suicide poses to society.

Why the Church Opposes Euthanasia

In common with a longstanding tradition of Western civilization, the Church believes that dying naturally is a vital part of life’s journey, in many ways the most meaningful part. Dying is a process of healing. Important things happen on that journey, and suffering and pain are often a part of it.

Dying is a highly meaningful gradual process of renunciation and surrender. Although some die swiftly and painlessly, it involves great suffering, because (and this is true of old age in general) it involves letting go of those things which in our lives we believe make us worthwhile and loveable: our looks, intelligence, abilities, and capabilities. This is what the great Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung called “necessary suffering,” the suffering endured by the ego, which protests at having to change and surrender. The idea that this kind of suffering is a vital part of growth is not a uniquely “religious” view, although Christianity — with the Cross and the Resurrection at its heart — has perhaps a richer theological understanding than most secular outlooks.

Yet while the Church urges the need to accept necessary suffering, it works to relieve and avoid might be called “unnecessary suffering.” The abandonment and renunciation of illness and dying require loving support, and sophisticated palliative care. Excessive physical pain, and the loneliness of abandonment, can and should be avoided.

That is why it is church organizations, pioneered in the United Kingdom and the United States in the 1950s by the hospice movement founded by a Christian, Dame Cicely Saunders, have transformed the way society now cares for the dying. “Last days are not . . . lost days,” she declared. Rather than seeing themselves as burdensome and unwanted, people with terminal illness should be in circles of love and care where they will be valued and made comfortable. Hospices meet the needs of the dying much better than hospitals, which are not geared to those who no longer need treatment (where hospitals “cure,” hospices “care”). In their document, “To Live Each Day with Dignity,” the bishops note that “effective palliative care . . . allows patients to devote their attention to the unfinished business of their lives, to arrive at a sense of peace with God, with loved ones, and with themselves. No one should dismiss this time as useless or meaningless. Learning how to face this last stage of our earthly lives is one of the most important and meaningful things each of us will do, and caregivers who help people through this process are also doing enormously important work.”

The Church’s view is that hospices need to be extended and made more accessible, such that no one ever needs to die alone and in severe pain.

As the U.S. bishops’ statement notes:

When we grow old or sick and we are tempted to lose heart, we should be surrounded by people who ask ‘How can we help?’ We deserve to grow old in a society that views our cares and needs with a compassion grounded in respect, offering genuine support in our final days. The choices we make together now will decide whether this is the kind of caring society we will leave to future generations. We can help build a world in which love is stronger than death.

This is not, it should be clear, about extending a life unnecessarily. It is not right to zealously provide burdensome treatment to extend a life when it is disproportionate to the relief it brings. Pain management — the specialism of hospice care — may even, as an unwanted side-effect, shorten a life. But if the intention is not to kill but to alleviate suffering, even when hastening death is foreseen, that is not euthanasia. The purpose of palliative care is to provide an environment of love and support for a person on his or her final journey.

But what of those who claim dying has no meaning beyond ending life, for whom the indignity associated with the process should at all costs be avoided, whether or not it involves intense suffering? Advocates of a change in the law see this is a classic case of religious people trying to impose their own norms on other people through the coercive power of the state. After all, they argue, an assisted dying law does not prevent anyone choosing, should they wish, to die a “natural” death.

But the Church’s opposition to assisted dying is not an attempt to persuade people of no faith to adopt a religious view of death. The Church’s opposition relies on a view of the common good of society, and how legalizing assisted suicide would undermine that good. It argues that the effect of an assisted suicide law is directly to undermine the dignity of the dying. As the U.S. bishops put it: “The assisted suicide agenda promotes a narrow and distorted notion of freedom, by creating an expectation that certain people, unlike others, will be served by being helped to choose death. Many people with illnesses and disabilities who struggle against great odds for their genuine rights — the right to adequate health care and housing, opportunities for work and mobility, and so on — are deservedly suspicious when the freedom society most eagerly offers them is the ‘freedom’ to take their lives.”

They add: “Those who choose to live may . . . be seen as selfish or irrational, as a needless burden on others, and even be encouraged to view themselves that way.”

Just as with abortion of capital punishment, the law cannot, in practice, be neutral; either the law regards death as a form of therapy, or it upholds the sacredness of all life. If participating in a suicide is legally and ethically acceptable it can only be because there’s aright to suicide; and once the state declares such a right, the arguments for confining it to the dying will seem arbitrary at best, and choosing to allow God or nature to take its course would soon come to be regarded as optional, eccentric, and even selfish.

These arguments about the effects of an assisted-suicide law are not abstract, for there is now plenty of evidence in countries and states that have allowed it for those claims to be tested. What each shows is that licensing assisted suicide in order to accommodate the wishes of a very small number of people is an illusion. In each case, the underlying dynamic of the law is changed — with lethal consequences. “We see evidence here not only of a practical slippery slope but a relentlessly logical slide,” writes Dr. Aaron Kheriaty inFirst Things, “from a cancer patient with six months to live to people who are merely unhappy, demoralized, dejected, depressed or desperate. If assisted suicide is a good, why limit it to only a select few?”

In a backgrounder arguing “Always Care, Never Kill,” Ryan T. Anderson argues that assisted suicide does four unacceptable things:

- It endangers the weak and the vulnerable. “People who deserve society’s assistance are instead offered accelerated death.”

- It corrupts the practice of medicine and the doctor-patient relationship, by using the “tools of healing” as “techniques for killing.”

- It compromises the family and intergenerational commitments. Legal assisted suicide sends the message that those who are elderly or disabled are burdens. “Physician-assisted suicide undermines social solidarity and true compassion.”

- It betrays human dignity and equality before the law. “Classifying a subgroup of people as legally eligible to be killed violates our nation’s commitment to equality before the law — showing profound disrespect for and callousness to those who will be judged to have lives no longer ‘worth living,’ not least the frail elderly, the demented, and the disabled.” It makes arguing for a right to life incoherent as it becomes inconsistent.

Lethal Logic: A Warning from Belgium and Holland

These are not hypothetical fears. The dangers of the inevitable slide of this logic can be seen in the experience of physician-assisted suicide in Belgium and the Netherlands. After considering the evidence, Dr. Paul McHugh, a professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, believes that “with physician-assisted suicide, many people – some not terminally ill, but instead demoralized, depressed and bewildered — die before their time.”

In 2001, the Netherlands was the first country in the world to legalize euthanasia and, along with it, assisted suicide. Various ‘safeguards’ were put in place to show who should qualify, and doctors acting in accordance with these ‘safeguards’ would not be prosecuted. For five years after the law became effective, physician-induced deaths remained level — and even fell in some years. The experts reviewing the figures concluded in 2007 that there was no “slippery slope.”

But it turned out that the stabilization in the numbers was just a temporary pause. Beginning in 2008, the numbers of these deaths began to increase by 15 percent annually, year after year. The annual report of the committees for 2012 recorded 4,188 cases (compared with 1,882 in 2002), and was expected to reach 6,000 in 2015. Euthanasia is on the way to become a ‘default’ mode of dying for cancer patients.

Professor Theo Boer, a Dutch ethicist who argued at the time in favor of a ‘good euthanasia law’ that would keep numbers low, was one of those reviewing the figures who changed his mind. “Now, with 12 years of experience, I take a very different view,” he says. He now believes that the very existence of a euthanasia law turns assisted suicide from a last resort into a normal procedure. After reviewing over 4,000 cases, he writes:

Cases have been reported in which a large part of the suffering of those given euthanasia or assisted suicide consisted in being aged, lonely or bereaved. Some of these patients could have lived for years or decades. Pressure on doctors to conform to patients’ – or in some cases relatives’ – wishes can be intense. Pressure from relatives, in combination with a patient’s concern for their wellbeing, is in some cases an important factor behind a euthanasia request.

More than half the cases of physician-assisted suicide in the Netherlands are involuntary. Government surveys found that as many as 650 infants a year have been killed by doctors, including those deemed to be facing a life of severe suffering with no prospect of improvement. Few prosecutions have ever taken place, because the doctors have applied the logic of the law. If it’s appropriate to kill someone with a terminal disease when they request it, is it so inappropriate to kill one who cannot express a view either way?

As Dr. Ezekial Emanuel, a key adviser to the construction of the Barack Obama administration’s health-care law, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly, “the Netherlands studies fail to demonstrate that permitting physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia will not lead to the nonvoluntary euthanasia of children, the demented, the mentally ill, the old, and others. Indeed, the persistence of abuse and the violation of safeguards, despite publicity and condemnation, suggest that the feared consequences of legalization are exactly its inherent consequences.”

In Belgium, which legalized euthanasia in 2002, cases rose from 24 in 2002 to 1,432 in 2012. In 2011-2012, 75% of the cases were for cancer (including all malignancies), 7% were for progressive neuromuscular disorders (multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, etc.) and 18% were for ‘other conditions.’

The trend is clear: euthanasia in Belgium and Holland has become part of normal medical care.

Doubling Down on Death in Oregon

While eroding a general culture of life, euthanasia corrodes due diligence in health care.

In Oregon, where assisted suicide has been legal since 1998, cases have gone from 16 in 1998 to 71 in 2011, an increase of 450 percent. The reasons why people take their lives under the state’s Death With Dignity Act reflect existential issues around loss — of autonomy, of enjoyment of life’s activities, of dignity — rather than pain, which doesn’t make it into the top five reasons given. Fewer than 6 percent of the 752 reported cases of individuals who have died by assisted suicide under Oregon’s law were referred for psychiatric evaluation prior to their death despite the fact that most suicides are associated with clinical depression or other treatable mental disorders.

Once suicide is seen as a good – and even celebrated (Brittany Maynard has been applauded for her “inspiring” and courageous” example – one of CNN’s “11 Extraordinary People of 2014” — in choosing assisted suicide) it has copycat effects. At a time when suicide rates are the third leading cause of death for adolescents and young adults according to the Centers of Disease Control, making suicide legal in any context threatens more than the sick and old, but anyone feeling alone or a burden. According to Oregon Public Health numbers, the state’s suicide rates had declined in the 1990s, only to increase “significantly” between 2000 and 2010, “now 35 percent higher than the natural average.”

In a reflection he wrote six months before his death from cancer in November 2011 and later published in the U.K. daily The Independent, Christopher Jones offered his own experience to help British lawmakers decide whether to follow Oregon’s example. He described the rollercoaster of emotions he felt following his diagnosis in 2009. After being first told he had colon cancer, he was then declared cancer-free, only to be diagnosed with cancer of liver only months later. Further operations revealed more tumors.

[A]t three periods – the diagnosis of secondary cancer, the traumatic experience of chemotherapy, and the prognosis of incurability – I was subject to extreme stress and a sense of hopelessness, and I might have been open to the option of ending my life by legal means, had these existed. The legal prohibition of this course was immensely helpful in removing it as a live option, thus constraining me to respond to my situation more creatively and hopefully. In hindsight, I now know that had I taken this course, I would have been denied the unexpected and joyful experience of being ‘recalled to life’ as I now am ….

As well as prescribing sanctions when offences are committed, law has directive and preventative effects. By setting boundaries, they help to maintain an environment of healthy ethics, good practice and positive expectations. A nakedly individualist account of decisions about the ending of life neglects or under-estimates this context. In the light of my experience, it is of prime importance that the law should signal the priority of the preservation of life — not at all costs but as the default option which requires adequate reasons to be overridden ….

A life-threatening or terminal illness is a process with many imponderable and unpredictable elements. There is great danger in attaching decisive significance to a person’s judgment at a particular stage in the process that their life is no longer worth living and ought to be ended, as both the situation and their feelings about it may change drastically in a relatively short period of time. …

[M]y experience has reinforced my conviction that the law prohibiting assisted suicide is an essential bulwark against well-meaning but unwarranted judgments about the value of life and the desirability of ending it in order to minimize or eliminate suffering. In my view, suffering is inescapable in this situation, and ought not to be allowed to trump all other considerations, especially when palliative care is taken into account.

A Call for Better End-of-Life Care

The testimony of the widow of the late Democratic Senator Edward M. Kennedy was one reason why assisted suicide failed to become law in Massachusetts in 2012. In her oped, Victoria Reggie Kennedy painted a less rosy view of an assisted death than campaigners had suggested. “Most of us wish for a good and happy death, with as little pain as possible, surrounded by loved ones, perhaps with a doctor and/or clergyman at our bedside,” she wrote. With assisted suicide, she wrote: “what you get instead is a prescription for up to 100 capsules, dispensed by a pharmacist, taken without medical supervision, followed by death, perhaps alone. That seems harsh and extreme to me.”

Her husband was told he had only two or four months to live yet went to live “15 months of cherished memories — memories of family dinners and songfests with our children and grandchildren; memories of laughter and, yes, tears; memories of life that neither I nor my husband would have traded for anything in the world.”

It is axiomatic in the advocates’ arguments that the individual must be the first and only judge of when the time is right for dying; and that those who feel they are a burden to others should be released from that feeling. This is consistently the major reason for seeking an assisted death. The Washington State Department of Health’s annual report on its own “Death with Dignity Act” records that 61 percent of those who received lethal drugs in Washington in 2013 reported “feeling a burden on family, friends and care-givers.”

The question that needs to be answered, therefore, is this: Do we as a society wish to agree with those who consider themselves to be a burden on it, and kill them at their request?

Baroness Ilora Finlay, a British professor in palliative care and campaigner against assisted suicide, argues that people with such feelings are by definition vulnerable, and the vulnerable need defending. “In reality, the vast majority of people facing dying are ambivalent, oscillating between hopelessness and hope, worrying about being a financial or personal burden on those they love or that their own care costs will erode their descendants’ inheritance. In a word, they are vulnerable, and it is a primary purpose of any law to protect the weak and vulnerable, rather than to give rights to the strong and determined at their expense.”

Keeping assisted suicide illegal is the best way of protecting the disabled, elderly, sick, depressed, or other vulnerable people from ending their lives for fear of being a financial, emotional, or care burden upon others.

But society must accept the implications of caring for the vulnerable. ‘No’ to assisted suicide is also a pledge to work for better care for the elderly and ill.

As Pope Francis told the Pontifical Academy for Life in 2015: “Abandonment is the most serious ‘illness’ of the elderly, and also the greatest injustice they can be subjected to.”

Better care for the elderly means investing in hospice care, which since the 1970s has revolutionized the relief of extreme pain and raised standards for the elderly care. The biggest threat to that improvement is assisted suicide.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, palliative-care provisions falls far below standards elsewhere. The architect of the 2001 Dutch euthanasia law, Els Borst, admitted in 2009 that the government of the time was wrong to have introduced euthanasia without improving palliative care. The Netherlands should be a warning to other countries. Persistent requests for euthanasia are very rare if people are properly cared for. But it’s harder properly to care for people once euthanasia is allowed. Assisted suicide chills the environment for the dying, encouraging people to seek death as an alternative to the suffering they fear, or the burden they are worried they will be on others.

Government programs and private insurers may even limit support for care that could extend life, while emphasizing the “cost-effective” solution of a doctor-prescribed death. The reason for such trends is easy to understand. Why would medical professionals spend a lifetime developing the empathy and skills needed for the difficult but important task of providing optimum care, once society has authorized a “solution” for suffering patients that requires no skill at all? Once some people have become candidates for the inexpensive treatment of assisted suicide, public and private payers for health coverage also find it easy to direct life-affirming resources elsewhere.

Rather than defend the status quo, therefore, we need to be passionate reformers in the direction of improving the quality of the journey at the end of life.

As Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Pro-Life Activities, said at the June 2011 release of the U.S. bishops’ first comprehensive policy statement on assisted suicide: “Compassion isn’t to say, ‘Here’s a pill.’ It’s to show people the ways we can assist you, up until the time the Lord calls you.”

And here’s how Cardinal Sean O’Malley put it after Massachusetts defeated a physician-assisted suicide bill: “Just as in our struggle against abortion, it is not enough simply to condemn abortion, but we need to help to take care of the women whose lives are in turmoil because of a pregnancy. In the same way, we need to reach out to those facing difficulties at the end of life.”

Doctors and nurses who work in end-of-life care know that there are many myths about dying. One is that doctors “speed up” the process by giving massive, fatal doses of morphine. In fact morphine can extend life by controlling pain and breathlessness and making patients comfortable. Morphine does not kill. Just because there is the last dose of a drug does not mean that the drug causes death (you might as well blame the last cup of water). Equally, the removal of life support — apparatus to assist breathing, or kidney or liver functions — does not cause death; when doctors decide to discontinue treatment, it is to allow the process of dying to take place, because death cannot be prevented. An end-of-life decision is different from a life-ending decision.

Doctors are trained to understand and manage the all-important transition from, on the one hand, treating a patient — supporting a body’s functions long enough to allow a person to recover — and, on the other, acknowledging that treatment is futile and not trying to block the natural process of dying. A doctor’s role — supported by the Hippocratic oath — is to support life as long as life has a chance. No wonder the medical profession overwhelmingly opposes assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Perhaps the most potent myth — and one that drives the call for assisted suicide — is that deaths are painful and difficult, yet most are not; or that deaths always require the prescription of opiate drugs, when they do not. In fact, most deaths are comfortable, if spiritually and emotionally demanding on everyone involved.

As Sr. Constance Veit of the Little Sisters of the Poor, who run homes throughout the world serving the elderly poor, the old person, writhing with pain, crying out for death is completely foreign to her three decades doing the work of caring for the sick and dying.

Yet deaths are not, on the other hand, “dignified.” The advocates of assisted suicide appeal constantly to this idea of “dignity in death” — as something rational and controlled, like a decision to jump in the sea before the boat hits the rocks. Dying involves renunciation, pain, and many indignities. We are not in control. And it calls forth compassion — ”suffering with” — in those who love and care for the person dying. Assisting a suicide is a corruption of compassion. A state that endorses it is creating an ominous new option that will rapidly undermine the sacred value of life itself. Rejecting it is the greatest act of compassion we can make for the elderly — while working for their real dignity.

Existing Frame

“A dignified death, free of pain at a moment of our own choosing is now possible. Given that medicine now keeps us alive for years, why not use medicine to decide to bring forward a painful death, ensuring that proper guards are in place? No one has the right to tell someone suffering that they should prolong their lives, especially for people who have no religious view of death. In cases of terminal illness, when a person is depressed and feeling a burden, why should they not be allowed to relieve themselves and others of the burden of staying alive, and opt for a dignified death? There should be a law to allow mentally competent, terminally ill people who see no point in suffering to choose the time and manner of their departure.”

Reframe

Assisted suicide is the wrong response to advances in medicine that prolong life. We need to spread palliative and hospice care that allows people to discover their true worth in spite of their illness and diminishment. Assisted suicide produces a logic of death that quickly corrodes society and the health-care profession. It makes the elderly and the disabled gravely vulnerable, while reinforcing messages that only the strong and successful lead lives worth living. Our response to those wanting to take their lives because they feel a burden should not be to confirm their suspicions, but to show them their true worth. That means working for truly dignified end-of-life care.

Key Messages

- Assisted suicide gives the green light to hopelessness and despair. It sanctions suicide as a response to hardship. The right to die becomes a duty to die.

- Assisted suicide leaves the vulnerable more vulnerable — especially the disabled, whose lives may be judged less valuable in law. It destroys the trust between doctor and patient.

- Assisted suicide undermines palliative care.

- Suffering does not diminish a person’s human value.

- Some suffering in life will be unavoidable; it is part of the process of dying. But no one should nowadays endure unbearable pain.

- The English-speaking world leads the globe in hospices and palliative care. We need more, not fewer, of these. People suffering/in pain should be offered real choice — the choice not to suffer unnecessarily, and to live their final journey as a time of spiritual healing.

- Rather than agreeing with those who believe they are a burden and killing them at their request, we should help people realize their worth and live lives of true dignity.

[The new edition of How to Defend the Faith Without Raising Your Voice is available in the U.S. from Our Sunday Visitor or Amazon, and in the U.K. from Amazon].

Tags: assisted dying, assisted suicide, euthanasia, suicide

thats a bunch of BS and you know it! people should have the right to live and the right to DIE if they so choose

Excellent article…excellent words of truth…thank you sincerely for posting…very impressive case against assisted suicide…I fully agree…Only GOD may give and take life !

yet in war its acceptable to take LIFE! why is that? People should have the right to DIE

Excellent article…We must take a strong lesson from our great Eastern civilizations…the West now lacks basic Humanity..how very sad indeed to live in ‘a throw away culture’ where the vulnerable and elderly and ill people are treated like objects…we must learna good lesson from the Eastern Cultures…the Middle East and the Far East…to respect LIFE and have respect for the Human person…The West must try to regain it’s sense of Humanity again…and show respect for God’s Ethical Laws !

this is not about GOD it is about death with Dignity! how is it dignified to be a zombie and people care for you since they hang onto your dead flesh!