Anselm Kiefer: earth, history, art, transcendence

I didn’t really want to see the Anselm Kiefer exhibition at the Royal Academy. All I knew about him was that his paintings are, generally, brown. Call me shallow, but if I have an hour free for art in central London I want to see something colourful that will delight and lift the spirit. Thank goodness my friend Fr Martin Boland persuaded me to go.

Kiefer was born into a German Catholic family in 1945, at the very end of the Second World War. His whole art is a struggle to make sense not just of the tragedy of war and the Holocaust, but of the fragility and ambiguity of human life that haunted post-war Germany. The historical leads to the existential.

There is a constant yearning for transcendence, but to find this without losing touch with the scorched earth that is the place of this longing. So the recurring symbols of transcendence sit within or hover above the mundane. Mythological swords are scattered in paintings of Kiefer’s attic studio. Three chairs, side by side, representing “The Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit” (the words are scrawled onto the canvas), float above a dark forest – a fire burning on each of the three seats. Gigantic sunflowers grow around the sleeping or dead body of Kiefer himself, representing both the search for the divine and the apparent impossibility of finding it, as they droop back down to earth under the weight of their bulbous heads.

For me, the most powerful piece is an installation made especially for this exhibition at the Royal Academy called Ages of the World. In the centre of the central octagonal gallery is a huge pile of what seems to be junk from the artist’s studio, rising above the viewer to 12 or 13 feet. Discarded canvases, many with painted images; film-strip negatives from old projects; the ubiquitous sunflowers – real ones – dark, desiccated, now horizontal; books; rocks; dust. (Sorry I can’t find a copyright-free image of this; but perhaps it would spoil it seeing it 2D).

It could have been so facile. But the title of the piece, and the wall panels either side, invite you to see this as a symbol of the whole of creation, with each layer representing a stage in the evolution of the universe and then of the earth. You begin to appreciate the carefully chosen symbols of the inorganic (rock, dust), the organic (sunflowers), the human (faces on the canvases and in the negatives), and the spiritual (the act of creativity within the discarded artworks themselves).

Never before have I had such a powerful sense of the wholeness of the whole of creation, and of the extraordinary ability of human beings to take a perspective on this wholeness, to somehow comprehend it and symbolise it and stand outside it in contemplation even while remaining firmly planted within it: not in the photos from the Hubble telescope, not in the opening liturgy of the Easter vigil (“All time belongs to Him, and all the ages…”), not in the Romantic experience of the sublime from the top of a mountain or the edge of the Grand Canyon.

To contemplate the world and the very existence of existence in this way was almost an out-of-body experience for me. It shows the near-miraculous quality of the human capacity for self-reflection and self-consciousness: to stand outside oneself and one’s world, to take a view from afar.

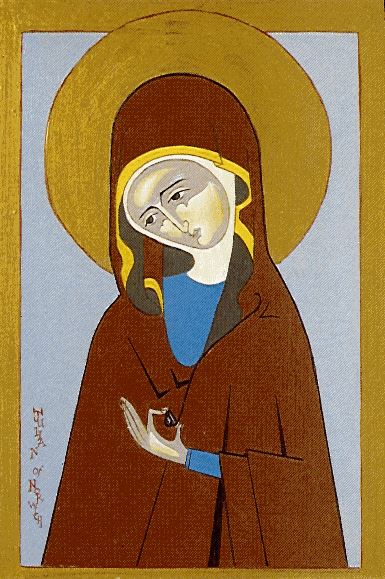

Julian of Norwich came to mind, the English anchorite and mystic, and in particular the well-known passage about the hazel nut (see the image above):

“And in this he showed me a little thing, the quantity of a hazelnut, lying in the palm of my hand, it seemed, and it was as round as any ball. I looked thereupon with the eye of my understanding, and I thought, ‘What may this be?’ And it was answered generally thus: ‘It is all that is made.’ I wondered how it could last, for I thought it might suddenly fall to nothing for little cause. And I was answered in my understanding: ‘It lasts and ever shall, for God loves it; and so everything has its beginning by the love of God.’ In this little thing I saw three properties; the first is that God made it; the second is that God loves it; and the third is that God keeps it.”

[“And in þis he shewed me a lytil thyng þe quantite of a hasyl nott. lyeng in þe pawme of my hand as it had semed. and it was as rownde as eny ball. I loked þer upon wt þe eye of my vnderstondyng. and I þought what may þis be. and it was answered generally thus. It is all þat is made. I merueled howe it myght laste. for me þought it myght sodenly haue fall to nought for lytyllhed. & I was answered in my vnderstondyng. It lastyth & euer shall for god louyth it. and so hath all thyng his begynning by þe loue of god. In this lytyll thyng I sawe thre propertees. The fyrst is. þt god made it. þe secunde is þet god louyth it. & þe þrid is. þat god kepith it.”]

Julian and Kiefer seem to be kindred spirits. The whole exhibition is really a meditation on “all that is made”, and on the mystery of “how it could last” when “it might suddenly fall to nothing for little cause”; and when in mid-twentieth century Europe it did seem as if it were falling to nothing.

The exhibition continues until 14 December. See the Royal Academy website here.

Tags: Ages of the World, Anselm Kiefer, featured, Julian of Norwich