Mitochondrial transfer: science that crosses lines for no good purpose

Three-parent embryos are the most high-profile recent development in reproductive technology, and an area where the UK is striving to take a leading role — hence the government consultation on new rules to allow it. Scientists, as always when seeking permission to push the boundaries of the law, say it offers hope of preventing life-threatening diseases for which there are no cures. But when it comes to biotechnology, ‘can’ does not imply ‘ought’. Both the technique, and the claims, need to be looked at very closely.

What the technique involves

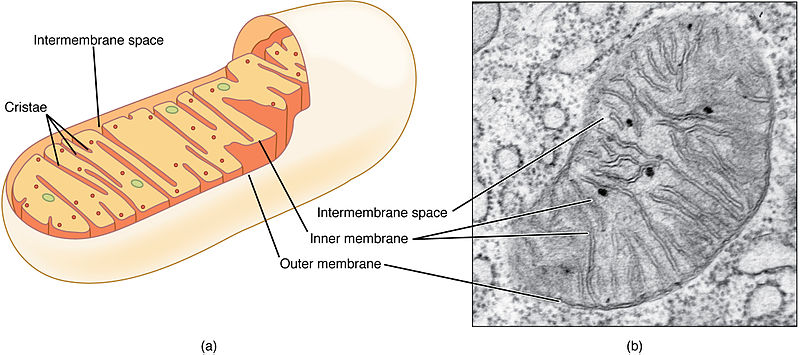

By replacing defective genetic material with that of a healthy, third-party donor, three-parent embryos aim to eliminate certain types of inheritable disease caused by defective mitochondria, the structures which generate energy within cells. About one in 200 children born in the UK have some form of mitochondrial disorder, the most serious of which affect the heart, brain, muscles and liver.

Under the procedure, the nucleus is removed from an affected woman’s egg or from a cell in an embryo and transferred to a donor egg or embryo that has healthy mitochondria. ‘Mitochondrial transfer’, as the technique is known, has never been tried in humans and is at the moment illegal — prohibited in Britain under laws that ban the placing of an egg or embyro into a woman if the DNA has been altered.

The UK is currently on track to become the first country in the world to introduce mitochondrial transfer in clinical practice. This will allow a small number of women carrying a particular kind of defective mitochondria to have children free from mitochondrial disease but still genetically related to them.

The proposed procedure is not a treatment for mitochondrial disease; it is a method of ensuring that individuals who would have had mitochondrial disease are not born. It does nothing to help the estimated 12,000 people in the UK already living with mitochondrial disease, or those yet to be born with it (often defective mitochondria is not identified until after the child of a carrier begins displaying symptoms). Nor does it help those with conditions which are only partially caused by defective mitochondria.

As a result of the technique, a baby will have DNA from the biological parents and a female donor who provides healthy mitochondria, the tiny biological batteries that power most cells in the body. The fraction of a cell’s DNA that is in mitochondria is minuscule and affects only how cells are powered. It does not influence the child’s physical appearance or personality.

Why the government is consulting

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, which governs the use of reproductive technology in the UK, prohibits the creation and use of genetically altered eggs and embryos except in the case of severe mitochondrial disease. The Department of Health’s public consultation is seeking approval for draft regulations which would introduce the use of mitochondrial transfer as a treatment in the UK. Parliament must approve those regulations before the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) can allow clinics to offer the treatment.

The scope of the consultation is to decide which of the two processes of mitochondrial transfer – pro-nuclear transfer or maternal spindle cell transfer – should be used, and how the practice should be licensed and regulated. The question of whether or not the procedure should be introduced at all, as far as the Department of Health is concerned, has already been settled.

Crossing a line

The desire to have one’s own children is a very human one. But meeting that desire through mitochondrial transfer would come at disproportionate medical and ethical cost. The human germline, the sequences of cells through which genetic information is passed on through generations, would be irrevocably altered. In introducing the technique, the UK will cross an internationally observed ethical and legal boundary, and in doing so gravely undermine the inherent dignity of the human person.

International consensus currently holds that genetic therapies which make structural repairs to a single individual, without affecting their genetic descendants, are ethically and medically justified if used with appropriate safeguards. But gene therapies such as mitochondrial transfer, which make modifications to an individual which will then be passed on through the germline, are not.

There is good reason for this. Mitochondrial DNA (or mtDNA), while comprising only a small percentage of a person’s total genetic material, is remarkably poorly understood considering the pervasive effects it has on human metabolism and development. Modifications made to a person’s mtDNA will become an irremovable part of the human germline, and will be passed on to that person’s descendants together with any undetected defects and unpredicted consequences that occur as a result.

What consequences? No one is quite sure. An advisory committee to the US Food and Drug Administration recently raised a number of concerns about lack of robust preclinical data on the safety and effects of the procedure. Trials at Newcastle University in 2010, which form the Department of Health’s evidence base, concluded that the average amount of defective mtDNA that remained after mitochondrial transfer was not significant enough to cause disease. But this gives no indication of the likelihood of defects and complications manifesting themselves at later stages of an individual’s development.

In other trials performed on macaques, which indicated that manipulated embryos can develop healthily, researchers observed considerable differences between outcomes for macaque and human embryos which cast doubts on the application and relevance of these findings to procedures on humans.

But the potential problems for modified individuals are not solely physical. It is unclear what identity issues modified children may experience in adulthood, given they will have at least three genetic parents, and in the case of PNT children no immediate genetic precursors.

As the Anscombe Bioethics Centre says in their paper on the subject, “we are very far from the unconditional welcome of new life which having a baby should involve.” This complex fragmentation of one of the critical building-blocks of human community, parenthood, is not something to be undertaken lightly.

The practice of pro-nuclear transfer, where the implanted embryo is constructed from components of prior embryos, shows this disregard for the natural value of human life particularly acutely.

The procedure will require the destruction of at least two embryos even in the most efficient model, and in reality it is likely to require more: the Newcastle University research found that embryos created by PNT were only half as likely to survive to the blastocyst stage as non-modified ones.

Contrary to the position of the Department of Health, no amount of regulation and safeguarding can make mitochondrial transfer a safe or ethical procedure. Its problems are inherent, and can be avoided only by prohibiting the practice entirely.

Instead, funding and efforts should focus on research into the causes of mitochondrial disease, and the development of treatments for individuals both living and yet to be born with these debilitating and poorly-understood conditions.

Pushing boundaries to the benefit of the few

Once regulations are introduced, it will fall to the HFEA to determine which women carrying defective mitochondria are eligible for transfer, based on the likely risk of significant impairment in any naturally conceived children. According to the Department of Health there would only be an estimated 10 cases a year severe enough to be eligible for the procedure. That leaves several hundred people being born each year with mitochondrial disease who still require care, treatment and assistance.

The introduction of mitochondrial transfer shows a growing tendency in reproductive technology to sideline conventional and established treatments in favour of research that pushes boundaries but delivers no greater clinical or social benefit. Just look at that happened with cybrids, introduced in 2008, whose clinical and research applications have turned out to be few and far between despite much initial hype.

People living with mitochondrial disease deserve safe and effective medical treatment and an understanding of what causes their condition. But mitochondrial transfer will not provide this. It aims to mitigate human suffering by simply preventing certain humans from being born, using methods that will have unknown and unquantifiable consequences for future generations. Introducing the practice into the UK will be a great step backwards for medical ethics and human dignity.

[Megan Hodder]

Tags: Mitochondrial transfer