Why keep the Sabbath?

Why should we keep the Sabbath? I know, because it’s there in the Bible; and it’s not just a throwaway line, it’s one of the Ten Commandments. But what is the reason given there for keeping the Sabbath?

It hadn’t struck me until morning meditation in the chapel recently that the two accounts of the giving of the Decalogue in the Old Testament offer two quite different explanations of why we should keep the Sabbath.

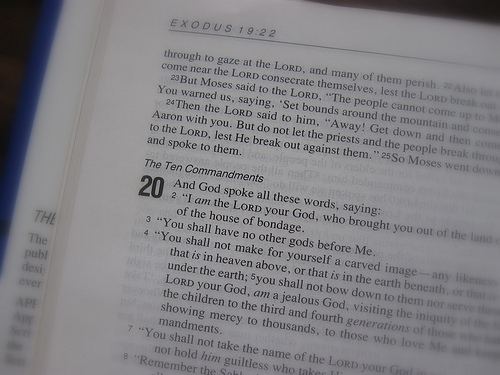

First, in the book of Exodus (Ch. 20), it’s about God and creation:

Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. For six days you shall labour and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. [But why?] For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it.

Then, in the book of Deuteronomy (Ch. 5), it’s about the Jewish people and their liberation from slavery in Egypt:

Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you. For six days you shall labour and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, or your son or your daughter, or your male or female slave, or your ox or your donkey, or any of your livestock, or the resident alien in your towns, so that your male and female slave may rest as well as you. [But why?] Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day.

So there are two different but complimentary meanings presented here. First, the day of rest tells us something about the nature of God himself. He is not just the creator, busying himself with his activity on behalf of the world – represented by the Six Days of Creation. He is not just defined in terms of his relationship with creation in general, or with us human beings in particular. He is also a God of rest, who exists in himself, and – as it were – for himself. His being, his self-sufficiency, comes ‘before’ his activity; and in the creation story his being, his resting, is the climax and fulfilment of that activity – although in God himself ‘being’ and ‘activity’ are all one, because there is a fundamental simplicity at the heart of everything that God is and does.

So the Sabbath, the day of rest, builds into the very rhythm of our week, and so into the structure of our very existence, a proper understanding of God. It shows us that his nature, and our ultimate destiny as sharing in that nature, is something completely beyond time, beyond temporal activity, beyond all the striving that we associate with a purposeful life.

But second, the day of rest, as presented in Deuteronomy, tells us something about our own nature as human beings – in so far as the liberation of the Jewish people from slavery in Egypt points to a more universal truth about the human condition. In this context, the Sabbath is a reminder that whatever freedom we have now is actually a gift – whether this freedom is social, political, moral, spiritual, religious, etc. We are free because God’s goodness, his mighty hand and outstretched arm, have given us this freedom – by creating us in the first place, and then by stepping into history to renew it. And it is our duty not just to remember this with thanksgiving, but also to use that freedom for good, and in a way that ultimately leads us back to the God who called us into freedom into the first place.

So the Sabbath ‘forces’ us to remember that we don’t belong to ourselves or completely determine the meaning of our own lives. Our life is given. Our freedom, to the extent that we can discover and live it, is given. That weekly moment of rest and letting go is in one sense a restriction, because we can’t do everything we would like to do; but in another sense it is the very foundation of all our activity and striving, because it helps us remember that this freedom is not something we can create for ourselves. There are many ways of making the Sabbath holy, but the primary meaning of the Sabbath lies in ‘consecrating’ the whole day, in setting it apart from the rest of the week.

Of course there are many other meanings to the Sabbath, many other ways in which it must be kept holy; and for Christians it is given a radical new meaning in the light of the Resurrection. These thoughts arise just from reflecting on the explanations given in the Decalogue. The Sabbath is about God and about us as human beings. It’s both a theology and an anthropology. We lay hold of all this simply by the discipline of letting go – as far as possible – of work and shopping for one day a week…

Tags: anthropology, Decalogue, Exodus, freedom, God, Holy Days, keeping the sabbat, liberation, Moses, Politics, Sabbath, Sunday, Ten Commandments, theology